May 28, 2015 Print

The world’s largest complete DNA analysis of ovarian cancer, published overnight in Nature, has revealed unprecedented new insight into the genetic twists and turns a deadly form of the disease takes to outsmart chemotherapy, potentially changing treatment approaches for women around the world.

Led by Professor David Bowtell from Melbourne’s Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, and in collaboration with researchers at Westmead Millennium Institute for Medical Research, Sydney, The University of Queensland’s Institute for Molecular Biosciences (IMB), Brisbane, and international colleagues, the study involved completely sequencing the genomes of 114 samples of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HSC) from 92 patients — collected either at diagnosis, following successful and unsuccessful treatment, or immediately after death — to intricately investigate how the cancer evolves to evade initially effective chemotherapy.

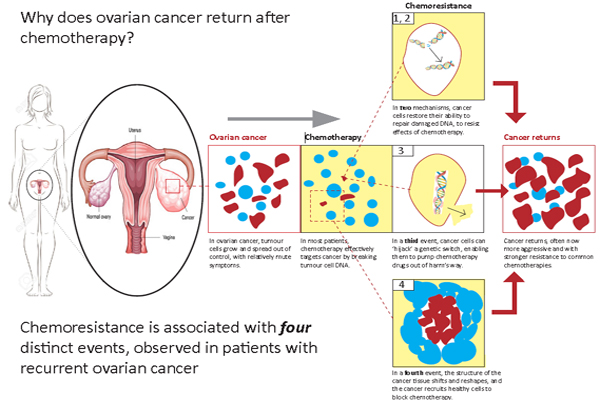

Professor Bowtell says the study revealed at least four key mechanisms by which initially vulnerable ovarian cancers go through genetic changes and become resistant to common chemotherapy.

“In two of the mechanisms, cancer cells find a way of restoring their ability to repair damaged DNA and thereby resist the effects of chemotherapy; in another, cancer cells “hijack” a genetic switch that enables them to pump chemotherapy drugs out of harm’s way.

“A further mechanism sees the molecular structure of the cancer tissue shift and reshape, such that sheets of “scar tissue” appear to block chemotherapy from reaching its target,” said Professor Bowtell.

HSC accounts for 70 per cent of all ovarian cancers, and 60 per cent of ovarian cancer-related deaths, claiming approximately 80,000 women globally each year.

Professor Bowtell says until now there has been little information to guide clinicians when selecting treatment for women whose cancer has returned.

“For decades clinicians around the world have watched HSCs shrink under attack from chemotherapy, before returning aggressively months or years later.

“By completely sequencing the cancers, sampled at different stages of disease, for the first time we can map their evolution under the selective pressure of chemotherapy and begin work on better interventions,” he said.

Professor Anna DeFazio, Head of the Gynaecological Oncology Research Group at the Westmead Millennium Institute and co-senior author on the paper, says the study could be practice-changing.

“Each of our findings suggest a refined approach to drug selection in recurrent ovarian cancer, which could include bypassing drugs that are unlikely to be effective.

“This particular view of such a complex disease has never been seen before, and we believe it will lead to more women receiving treatment better suited to their particular cancer, all over the world,’ said Professor deFazio.

Fellow co-senior author Professor Sean Grimmond from IMB says finding sub-types of disease, but also sub-types of resistant disease, carries huge implications for designing future treatments.

“We really need to continue to write the atlas for this complex disease and get more sophisticated about the amount of drug we give, when we give it, and the types and combinations of treatments in relation to each woman’s cancer,” said Professor Grimmond.

Dr Ann-Marie Patch, from QIMR Berghofer Medical Genomics Group and formerly from IMB, says cutting-edge technology was crucial to this turning-point in the global fight against ovarian cancer.

“By using the latest sequencing techniques we have been able to find scars from breaks in the DNA that have helped us better define the genes involved in allowing tumours to grow.

“The research team is incredibly appreciative of the many women who allowed their samples to be collected so that we can find out what happens to the cancer cells after treatment and will allow us to work towards better treatments for women in the future,” said Dr Patch.

The study involved women from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and Westmead Hospital in Australia, Hammersmith Hospital at the Imperial College of London, United Kingdom, and The University of Chicago, United States, and was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Worldwide Cancer Research (UK), Cancer Australia, Ovarian Cancer Action (UK) and Ovarian Cancer Australia.